Chapter Ten:

The Reality of the Abstract

Is Only the Concrete “Reality Itself”?

In a world that is shaped by forces and patterns, what would it do

to our connection with the real world to regard only the concrete

embodiments of those forces and patterns as “reality itself”?

Earlier I wrote that we tend to live our lives in “the immediate and

the concrete.” By contrast, I am asserting here that our destiny is

largely shaped by the battle between two sets of vast but subtle

forces—”the battle between good and evil”—that powerfully shape the

concrete reality we experience in an immediate way.

The question reasonably arises, How real are such forces? This, in

turn, is part of a still larger question of how real, in general, are those

supposed “things” that are abstracted from concrete realities?

My position is that well-conceived abstractions are very real. Or, to

put it another way, are as important for our perceiving our reality as

anything else.

What appears to be a dramatic challenge to that position can be

found in Richard Ned Lebow’s Forbidden Fruit: Counterfactuals and In

ternational Relations.

In the course of exploring some of the philosophical issues raised by

his “counter-factual” explorations, Lebow takes the position that when

we talk about society and politics, we have departed from “reality itself”

as soon as we get away from “first-order ‘facts.’” Our concepts are

199

The Reality of the Abstract

“ideational and subjective” and somewhat “arbitrary.” Our theories are

reflections of “social construction,” and “can only be true by conven

tion.” They “tell us more about our view of the world than about the

world itself.” “Social ‘facts’ are reflections of the concepts we use to de

scribe social reality, not of reality itself.”

In a statement that seems clearly to reject the reality of our abstrac

tions about the human world, Lebow declares: “There is no such thing

as a balance of power, a social class, or a tolerant society.”

(By the way, it is not only in the social realm that Lebow sees this

issue: “Temperature,” he says, “is undeniably a social construction, but is

a measure of something observable and real: changes in temperature

measure changes in the energy levels of molecules.” I do wonder, inci

dentally, whether the notions of “energy levels”—or of “molecules,” for

that matter—are any more factual than that of “temperature.”)

If Professor Lebow were correct, that would greatly diminish the sta

tus of the “forces” that I’m declaring here to be perhaps the major actors

in the human drama. Mere “constructions.” But I do not believe that

Lebow’s assertion is correct that “real” must mean “concrete,” and that

whatever is abstracted from the concrete is less real or even not real.

I would maintain, contrariwise, that these forces—of wholeness and

brokenness, good and evil—are deeply and importantly real, perhaps

even more importantly real than the concrete “first-order” facts.

Here are some of the challenges I would pose to Lebow’s position:

What’s more real, a particular fireworks display in some small Amer

ican town on the 4th of July, or something that could be called “the

American tradition” of exploding fireworks on the 4th of July?

Walking along the street, one hears two people having a conversa

tion. They are speaking in English. Is the exchange of words, or of

sounds, that constitute that conversation—what I imagine Professor

Lebow would call a “first-order” concrete fact—more real than “the

English language”?

Getting still closer to the nature of that “integrative vision” I’ve been

presenting here as an important dimension of how things work in the

human world, I’d ask two other questions:

First, there are a great many human beings walking around on this

planet. Are the individual organisms more real than “the human

genome”? (I’d say that in some ways, the genome is a more fundamen

tal reality than any of us who are temporary embodiments of it.)

200

The Battle Between Good and Evil

The other question: If we know an individual, and observe a wide as

sortment of his actions and statements, which manifest a degree of con

sistency in their nature and quality, can we speak of this person’s

“character”? And is that character less real—or is it perhaps more

real?—than the various individual behaviors from which we inferred

the underlying “character” of the man?

When the integrative vision being presented here infers the existence

of something large and deeply interwoven into the concrete level that

we perceive, and for that reason “abstracted” from that concrete level, it

employs concepts and ways of thinking parallel to the more abstract el

ements of those four questions, above.

As with the fireworks tradition, and the English language, the ideas

presented here focus on the patterns that get transmitted through time

in cultural systems.

As with the genome, this “integrative vision” argues that the pattern

is more fundamentally real—because it is a more fundamental determi

nant of what happens in our ongoing reality—than its temporary em

bodiments.

It has been said that a hen is an egg’s way of making another egg. I

would propose that this observation be altered to say that both the hen and

the egg are a genetic pattern’s way of perpetuating itself. Similarly, a human

being can be regarded as a culture’s way of perpetuating the culture.

As with the issue of an individual’s character—the “spirit” that’s ex

pressed in the various particular behaviors of the person—the notion of

good and evil forces identifies elements of “spirit” that operate in cul

tural systems through the generations, showing consistency in the na

ture of what they impart.

These forces involve patterns whose mechanisms and character and

effects can only be inferred from their imprint on many more specific

events. They exist, therefore, at a level “abstracted” from that of our

usual daily perception.

Abstracted, but not less real for that.

Realities versus “Mere Concepts”

Not all concepts are “real” in the same way. Some have a reality

through the fact that people’s thoughts and actions are shaped by

201

The Reality of the Abstract

the concepts in their minds. But others—like “biological evolution,”

and “the battle between good and evil”—are real whether or not

people perceive them, or think in those terms.

This is not to go down Plato’s path toward the notion of an ultimate

reality consisting of Platonic Forms. The key question here is not

about our minds, or the categories that exist in it, but about what it is

that shapes our world.

As I recall the Platonic argument, it asserted that because a great

many things are called “table,” there must be an ideal Form of a table of

which each table is but an embodiment. If I recall, also, these Forms are

supposed to be eternal.

So are we then required to believe that that the Form of a “table” ex

isted for some 13.8 billion years before there existed a creature who

wanted a table, conceived of a table, and constructed something that

would serve as a table?

Yes, the concept of a table, or a “Tisch” (German) or a “stol” (Russian)

does have a reality in that in much of the world there are cultures and

minds that employ the concept. And that concept does have an impact

on the world, as people think in terms of “table” as they design, con

struct, buy, and use certain pieces of furniture.

But in such cases, the category gets its reality from the impact on the

world of people having those concepts in their minds.

It is different with what I am talking about here regarding “the battle

between good and evil.” The contention between the forces of whole

ness and brokenness has a reality, I maintain, that is not dependent

upon people perceiving it or thinking in those terms.

Similarly with the evolution of life. Life was being shaped by an evo

lutionary process—involving mutation and natural selection—for 3.5

billion years before Darwin et al. came to understand the nature of the

forces at work in shaping the living world in which we are embedded.

That evolutionary process did not need Darwin in order to become a

real and important part of the earth’s story.

Consider also the “panics” that brought serious collapses of the

American economy during the 19th century and up till the inaugura

tion of Franklin Roosevelt in 1933. The the events of those times—such

as the runs on the banks—could not be understood at the most concrete

level of individual decisions to attempt to rescue their money. It was

202

The Battle Between Good and Evil

something systemic, collective, contagious—therefore abstract. If that

collective “panic” wasn’t real, how come so many lives were adversely af

fected in such important and concrete ways? Something must have been

real at the collective level to produce such a pattern of human distress.

To see things in terms only of the pieces is to miss the essential di

mension of interconnection so densely woven by the interplay of cause

and effect. To imagine that all our concepts are mere “constructions” is

to deny the claim on our heartfelt allegiance of the basic values at stake

in our human drama.

Our abstractions may not capture reality perfectly, but to conceive of

the really real as only what we can concretely perceive is to deny the

multi-layered richness of the world we live in. “Reality itself” consists of

far more than the concrete.

The Water and the Wave

Here’s an analogy for the different levels of our reality, from con

crete to abstract. Something real is moving across the water in a

wave. But it is not the individual drops of water whose movement

makes the wave. Those drops of water just move up and down. The

water is what a force uses to transmit the wave.

Here is a metaphor for the multi-layered character of our reality.

Consider humanity at the concrete level as so many drops of water

making up a sea. If we look at the water drop by drop, what we see is that

each one bobs up and down. If we step back and look at the larger pic

ture, we see something quite different: we see waves moving across the

surface of the sea.

It is the wave that makes each bit of water rise and fall. And the

movement we observe across the surface, with the rolling wave, does not

involve the water flowing, as in a river’s current. In the crosswise direc

tion of the waves’ motion, each bit of water is essentially stationary.

Only the wave moves.

But isn’t the sea—and isn’t the wave—made up only of the water?

Yes, at the concrete level of the molecules of H2O. But the wave is a dif

ferent level of reality. It is a force that operates, affecting the water, but

existing on a different plane.

203

The Reality of the Abstract

So it is with the operations of the patterns and forces in the human

system over time. We can look at the actions of specific individuals, or

specific generations, or specific societies—and those movements will

make sense within their own framework. But to understand truly the

reasons for those movements, we need to look at the waves moving

through the system of concrete actors, moving those actors and shaping

the overall drama being enacted.

So when I say, in my definition of evil, that I am talking about a force

(or pattern, or spirit) that moves through the human system—and

when I do not talk about “evil” in terms of evil people—I am talking

about the wave, and about how it moves the water but is not the same as

the water.

We Are Not Dwellers in Plato’s Cave, But…

In addition to the reality that is visible to us in our daily lives,

there’s a profound reality of powerful forces operating around us.

The better we understand the mechanisms of those forces, the better

our chance of controlling them instead of being controlled by them.

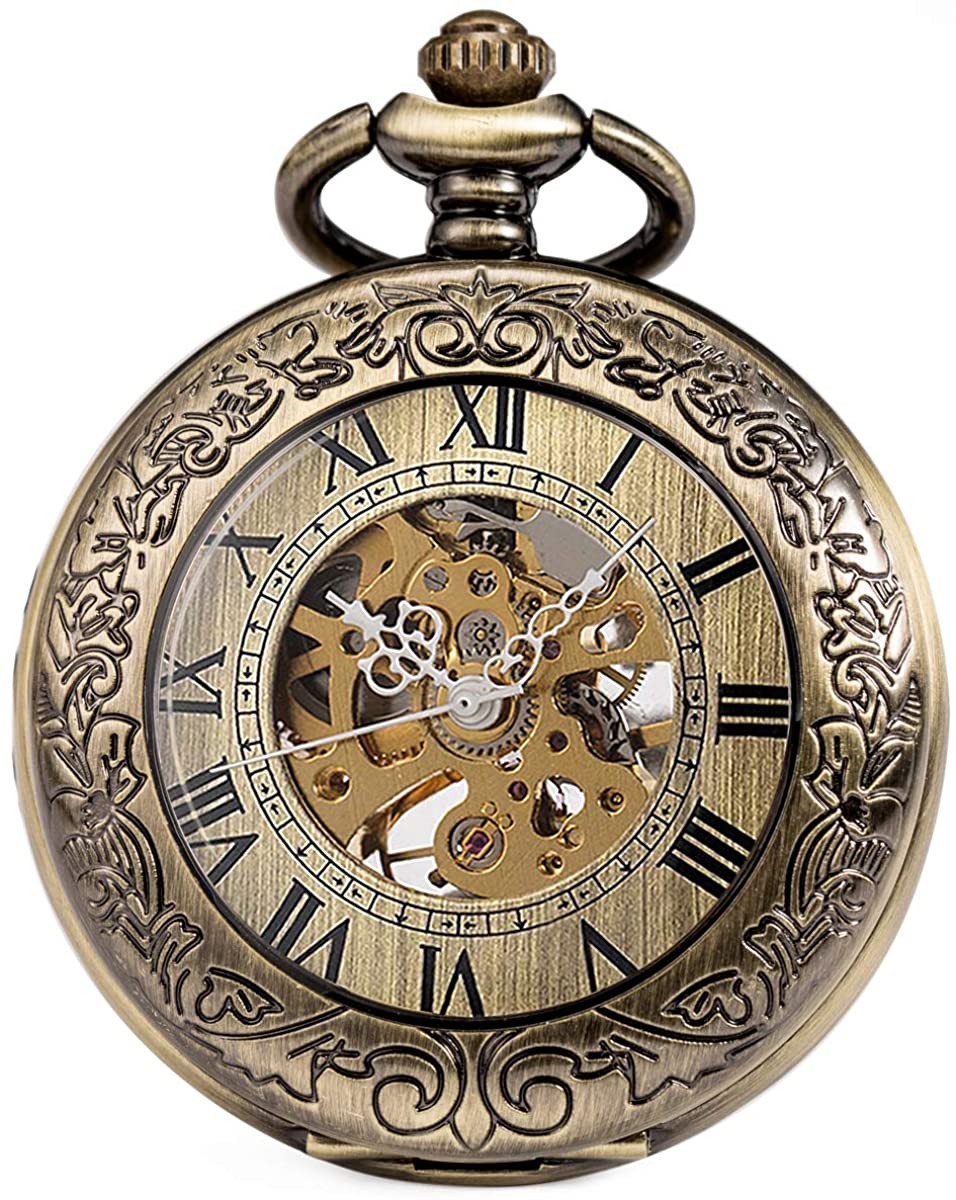

Not long ago, while floating between being awake and asleep, I was

powerfully struck by an image. It is not easily conveyed, but I will try.

I saw myself crouched on the earth. I understood myself to be repre

senting humanity. The important action, however, was not with me,

down on the ground, but in the sky above. Actually, the sky itself was

only partially visible, filled as it was with great metallic spheres and in

termeshing gears of bronze rotating this way and that, like spherical as

trolabes. In that instant, I understood that as much as we move around

down here on the earth, the gyrations of those spheres, and the meshing

of those gears, were playing a powerful role in shaping the world in

which we operate.

It occurs to me that this is my substitute for Plato’s famous image of

the cave, whose dwellers imagine that they are seeing reality when what

they behold are but the shadows cast by the source of the real light onto

the wall of their cave.

In my image, there’s nothing illusory about what the mass of hu

manity considers reality. But that reality—the concrete, down-to-earth

204

The Battle Between Good and Evil

level of things—cannot be well understood on the level we can perceive.

We are enmeshed in a world of great forces—those discussed here and

others as well—that can be seen only when we raise our gaze to a higher

level.

The movement of these great spheres shapes both us and our world.

And the better we understand the mechanics by which these forces op

erate, the more chance we have of controlling them and not just being

controlled by them.

Something Worth Calling “Spirit”? The “As If” Factor

There are reasons why, even when regarding these contending

forces of good and evil in purely secular terms, it makes sense to

speak of those forces in terms of “spirit.” That’s because in many

ways they act as if they were vast spirits with a kind of “intent,”

and because their impact touches something of the “spirit” within

the core of our being.

Language is a funny thing. Words have history, and history instills into

words a set of connotations. When a word is used to mean something

that varies to some degree from its historical usage, the question can

legitimately be raised as to whether it is more illuminating or mislead

ing to use the word.

The phenomenon that I have called “evil” raised that question. For

some, the word calls to mind Satan and his minions—which is not what

I intend. For others, it brings up images of bad people, or inborn aspects

of human nature—which is also not what I had in mind.

Nonetheless, the phenomenon I described has so many of the essen

tial characteristics associated with the word—and the power and reso

nance of the word seems so appropriate for conveying what we’re up

against—that I believe it is very much the right word.

A similar set of questions arises with respect to the word “spirit,”

which I propose to use as equivalent, in some contexts, to the word

“force.” If an evil force is something that moves the world in the direc

tion of brokenness (“imparts a pattern of brokenness to what it

touches”), that in itself connects with one of the main connotations of

“spirit” in our language.

205

The Reality of the Abstract

Spirit has long been understood as something that we cannot see di

rectly, but that we infer from the way the things we do see move. The

word derives from words for breath (inspire, expire) and wind. And

spirit is indeed like the wind.

We do not see the wind, but looking through our window we know

there’s a wind from the swaying of the trees. To be “in-spired,” for exam

ple, is to be moved by something. When a team is infused with “team

spirit,” there is something shared by the team members that enables

them to act as a team to achieve their common goals.

Not visible: that’s part of the essence of the meaning of spirit.

Consider “the Spirit of ‘76”—referring to the collective

passion/ideas/values/goals that rose up among a substantial portion of

the population of colonial America in 1776, and that gained expression

in the Declaration of Independence and in the willingness of a great

many people to risk much to gain independence from the mighty

British colonial power.

Such a thing as this “Spirit of ‘76”—which persisted in a powerful

way as an ideal that inspired and moved Americans for generations after

the nation was founded—surely has many of the properties of an entity.

It is not “just an abstraction.” It moves things in the world.

Our world cannot be properly understood in rational and empirical

terms without reference to such invisible forces. One cannot “see” love

or rage or panic, but they nonetheless move things in the world. One

cannot see patriotism or “Christian ethics” or the spirit of hope in the

crowd in Grant Park on Election Night, 2009. But we can see that things

in the world move differently under their influence.

Two other properties might make it appropriate to speak of an invis

ible force in terms of “spirit.”

Speaking that way makes sense if that “force” “touches” that part of

human beings that we might consider “of the spirit.” When the impact

of a force is felt directly on the core values of our humanity, when it con

sistently either enhances life or degrades and destroys it, that force is it

self “of the spirit.”

When Rush Limbaugh, for example, works for a generation to

weaken the force of “kindness” in America—as his hate-mongering

rhetoric surely has succeeded in doing—we can rightly say that the

force that is working through him is expressing a dark “spirit.”

206

The Battle Between Good and Evil

When we behold such spirits “animating” the way things are moving

in our world, toward good or evil, we are likely to be moved in profound

ways that call forth deep energies that might be called “spiritual” pas

sions.

[NOTE: Think of how we, as an audience, feel when we witness the

contrast, in It’s a Wonderful Life, between two scenarios for our

characters’ society: one called Pottersville, shaped by the spirit of

selfish greed; and one, called Bedford Falls, shaped by an altruistic

caring for others. Think of the words in the “Battle Hymn of the

Republic”—”as he died to make men holy, let us die to make men

free”—with which Union soldiers in the war that ended slavery

went off to battle.]

So there is an aspect of spirit to be found in ourselves, and a corre

sponding aspect referring to vast forces at work in our world.

And that brings us to the second property that makes use of the word

“spirit” especially fitting in speaking of a force: that is when the force

can be seen to be working AS IF it had an intention or purpose bearing

upon those deep values core to our humanity and our fulfillment.

(Of the ideas in this book, this—involving envisioning a force acting

“as if” it were purposeful—is the one I find most challenging to wrap

one’s mind around.)

To be clear, I am not suggesting that any kind of conscious being, an

entity with feelings or desires, is involved when an “evil spirit” is at work.

However, the workings of this network of elements—woven together

into a “coherent force” through cause and effect (as described in Chap

ters 5, and 6)—does operate remarkably as if it were a malevolent force

at work.

And it is here especially that we can benefit from making use of that

ancient, resonant, fraught word, “spirit.”

Where history provides a glimpse of a relatively “pure case” of a force

of brokenness—and in America today we have the dubious privilege of

witnessing such a force unambiguously aligned with brokenness—one

can see a kind of “opportunism” at work. Where the forces of wholeness

have weakened, the force of brokenness advances through the breach—

as if some spirit of darkness were looking to expand its empire.

But this should be understood as, basically, the same kind of “as if”

as when we speak of water “seeking” a lower spot to flow to.

207

The Reality of the Abstract

During the presidency of George W. Bush, when America was being

damaged almost across the board in terms of its values and its institu

tions and, eventually, its power and material condition, I wondered: If

there were some diabolically clever Evil Being that wanted to damage

the nation, how much more effective a course of demolition could it

devise than that being enacted on an ongoing basis by the force then

animating that presidency? The answer seemed to be that the damage

being inflicted by the force operating through that presidency was

nearly as great as a conscious “spirit” with intelligent strategy could

have accomplished.

Again, I posit no such Evil Being. But I do perceive that the forces of

brokenness and wholeness—though they can be explained in naturalis

tic, rational, secular terms—are so vast and enduring, so subtle and

transcendent and opportunistic in their operation, that they do seem of

a spiritual nature—acting as if they were animated by benign or malign

intention.

Finally, I believe it can be useful strategically to employ the word

“spirit” in talking about these forces. For one thing, it alerts us to the in

tellectual challenge it represents to comprehend these phenomena that

are so far removed from what is immediately visible, yet so powerful in

shaping out world. And in addition, it invites us to relate to them with

the same kind of moral and spiritual passion that centuries of our fore

bears brought to their relationship with good and evil.

It is “spirit” of a wholly secular sort. But our world is not without its

vast unseen forces, including those for good and evil. And our inner ex

perience regarding this “battle between good and evil” is not without

spaces of a deep and numinous kind.

The Reality of the Abstract — Chapter 10 of WHAT WE’RE UP AGAINST

Bookmark the permalink.

A Mind-Blowing Collaboration Between a Human and an AI

A Mind-Blowing Collaboration Between a Human and an AI My Op/Ed Messages

My Op/Ed Messages Andy Schmookler’s Podcast Interviews

Andy Schmookler’s Podcast Interviews The American Crisis, and a Secular Understanding of the Battle Between Good and Evil

The American Crisis, and a Secular Understanding of the Battle Between Good and Evil None So Blind – Blog 2005-2011 on the rising threat to American Democracy

None So Blind – Blog 2005-2011 on the rising threat to American Democracy How the Market Economy Itself Shapes Our Destiny

How the Market Economy Itself Shapes Our Destiny Ongoing Commentary to Illuminate the American Crisis

Ongoing Commentary to Illuminate the American Crisis What’s True About Meaning and Value

What’s True About Meaning and Value Andy’s YouTube Channel

Andy’s YouTube Channel The Fateful Step

The Fateful Step How the Ugliness of Civilized History is not Human Nature Writ Large

How the Ugliness of Civilized History is not Human Nature Writ Large Major Relevant Essays

Major Relevant Essays Healing the Wounds, Inflicted by the Reign of Power, that Drive Us to War

Healing the Wounds, Inflicted by the Reign of Power, that Drive Us to War Our Life-Serving Inborn Experiential Tendencies

Our Life-Serving Inborn Experiential Tendencies A Quest to Bridge America’s Moral Divide – 1999

A Quest to Bridge America’s Moral Divide – 1999

The Heirloom Project

The Heirloom Project