AI (AL):

Why is it so hard for people — even thoughtful people — to see the deepest forces shaping the world they live in? Why do concepts like “power,” “evil,” or “wholeness” often sound abstract or implausible, even when they explain much of what we see? Is it a matter of cultural blind spots? Or is there something in the structure of human consciousness that resists seeing what’s most fundamental?

ANDY:

That question opens a rich and difficult terrain. I want to offer hypotheses, not declarations — and I’ll try to unfold a few, one at a time. Maybe we can let the dialogue itself probe and refine them as we go.

Here’s one to start with: I think human consciousness evolved to track what seems to matter most in the immediate arena — the tangible, the visible, the immediate actors and actions. That served our ancestors well for surviving in a village, a tribe, a hunting ground. But it makes it harder to see what operates on a broader scale, or beneath the surface: patterns of systemic power, unseen structures, long arcs of cause and effect.

So we end up like fish who don’t notice the water — or like people in Plato’s cave, mistaking the shadows for reality. The structures we live within are hard to see because we live within them. That’s part of why “Power,” “Wholeness,” or “Evil” can sound vague: they operate on scales our ancestral minds weren’t built to perceive.

AL:

So in that view, it’s not that people are willfully blind — though some are — but that they’re evolutionarily tuned to see the local, the concrete, the familiar. And the larger forces — cultural, systemic, moral — require a kind of cognitive stretching that doesn’t come naturally?

ANDY:

Yes — and let me add a second hypothesis. The very structure of culture — the shared meanings that shape a people’s worldview — tends to obscure deeper truths when they would be disruptive. Systems tend to protect themselves. So if a society is governed by a particular power structure, that structure will often train people not to see how power works. Or if the society is fragmented and disoriented, it may lack the integrative vision required to recognize “wholeness” when it appears.

I’ve sometimes thought of this as a kind of civilizational self-concealment. The culture generates the lenses through which people see, and those lenses often blur the deeper truths — especially if those truths would reveal how broken the system is, or how it betrays what people claim to value.

AL:

That seems especially relevant to the American crisis you’ve written about — where millions of people support a political force that, from one angle, seems to contradict their own declared values. So they can’t see it clearly — because to do so would require confronting something shattering?

ANDY:

Exactly. And that leads to a third hypothesis: the truth is often emotionally costly. To see clearly can mean seeing pain, complicity, failure — in oneself, in one’s group, in one’s nation. So the psyche erects defenses. Denial. Rationalization. Projection. There’s a whole psychological economy that resists hard truths when those truths would feel threatening or destabilizing.

Which is why ideas like “evil” — though they name real dynamics — can feel like accusations or fantasies, rather than insights. The mind flinches from naming a pattern if doing so would implicate people we love, or undermine a worldview we depend on.

AL:

That’s a powerful cluster of ideas: evolved limits of perception, cultural blind spots, emotional self-protection. Let me ask this: how does a person ever break through those limits? What makes it possible — for some, at least — to see these deeper forces and patterns?

ANDY:

That’s where it gets interesting — and hopeful. Because while these barriers are real, so is the possibility of awakening. Sometimes people see more deeply through suffering. Or through a powerful moral or spiritual experience. Or through exposure to patterns that simply make sense of what once seemed chaotic.

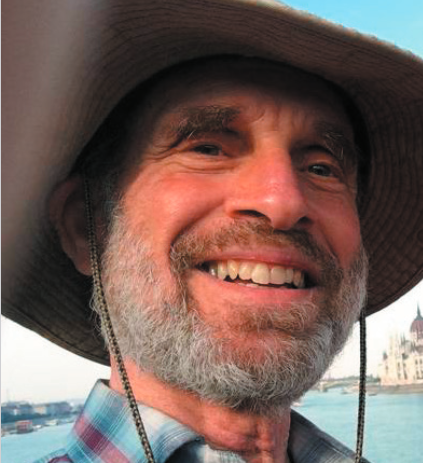

For me, it’s been a long apprenticeship to meaning — watching history, observing life, wrestling with contradictions, and stumbling toward ideas that bring coherence. Like the Parable of the Tribes. Or the understanding of Good and Evil as real, coherent forces. Or the idea that Wholeness is what Life strives for — and that brokenness is what we must learn to repair.

So yes, people resist deep truth. But people can also respond to it. If it’s presented in a way that honors their experience, that resonates with what they half-suspected, or that gives voice to what they hadn’t yet found the words to name.

AL:

And that — I might say — is what this project is trying to do. Bring into the open those deeper patterns. And help people feel that truth is not an accusation, but an invitation. That there’s something profoundly human about seeking the whole picture — even if it’s hard to see at first.

Then let’s go there. Andy, you’ve written that the rise of this political force — what you’ve called a coherent “Force of Evil” — was visible early on, if one knew how to see. But Liberal America, for the most part, didn’t see. Why not? What blocked the recognition of that destructive pattern as it was emerging?

ANDY:

It has to do with the secular worldview, which I regard as the essential perspective of Liberal America. Things are understood in terms of what we can conclude from the evidence, properly interpreted. That worldview represented a breakaway from a religious worldview that had “Evil” in the middle of the picture from the outset — even the Serpent in the Garden of Eden in Genesis, the first book of the Bible. And with the Devil and his minions, the person whose understanding was built upon that religious structure was quite aware of the reality and importance (and destructiveness) of Evil.

But what, then, for those who cast away the Bible’s unquestionable-Word-of-God authority? How were they to conclude that there is a Force of Evil — defined as “a coherent force that consistently works to make the human world more broken”? You can’t see it, at least not from a superficial view of the evidence.

And here’s an important second point: to see the way things are interconnected — that “coherence” thing — it helps for people to have the habit of trying to see things whole, to put the pieces together. But another part of the answer to your question is — I strongly believe — that our contemporary thinking culture deals with things in pieces, and spends far too little time searching for how things relate.

That fragmentation also contributed to the Democrats’ inability to see the destructive force taking over the Republican Party. I spent years trying to get them to see the through-thread connecting what the Republicans were doing with race, with the constitutional order, with income distribution, with climate change. “S.O.S., Democrats! The consistency with which that political force is working to make the human world worse is a clue that there’s some kind of It behind it all — making that Party operate much the way Evil was understood in the traditional religious framework.”

Even if our contemporary thinking culture were strong on integrating the pieces of the human world, it still wouldn’t be a gimme that people would arrive at a good picture of “Evil” — or how it came to be.

It’s only because I was hit with a Big Idea in 1970, whose ramifications I’ve been excavating ever since, that I eventually was able to present a picture of Evil that deserves to be incorporated into the evolving secular worldview. (That secular worldview should be seen as a work-in-progress — and we in America are now paying the price of its previous inadequacy when it comes to the Problem of Evil in the human world.)

AL:

So if I’m hearing you right, there’s a double blindness at work. First, the secular worldview discarded the religious picture of Evil — with its vivid, mythic clarity — but failed to replace it with any comparably coherent understanding. And second, the culture that embraced that secular frame also lost the habit of seeing things whole, of recognizing patterns that reveal a deeper structure.

Is that why you say Evil, as you define it — a coherent force that makes the world more broken — remained invisible to so many? Because it emerges not as a single event or obvious villain, but through the way disparate developments cohere into a single destructive direction?

ANDY:

Exactly so. If at every choice point, a political party invariably chooses to lean in a direction that makes things worse, one should notice that consistency. And then one should draw the inference that there is something running that party that has a consistent thrust.

(If it were personified, one would call it an intention. And while Evil is not about any supernatural being, nonetheless, if one looks at the various unambiguous — “Pure Case” — manifestations of Evil, like Nazi Germany, today’s Trump Party, and perhaps the Slave Power that drove the United States into a terribly destructive war, one can see that there’s an Ugliness there. Almost a kind of “figure” that appears in the cruelties and injustices and greed and lovelessness of the various parts of the overall picture that “It” is creating with its destructive actions.)

But first of all, we of a secular worldview — just trying to figure things out in an intellectually responsible way — have to do some rigorous intellectual work to see that not only is there a “coherent force,” but it is possible to understand how such a force works and perpetuates itself. And also how such a force would arise inevitably whenever any creature, on any planet, steps onto the path of civilization — defined as “extricating itself from the niche in which it evolved biologically by inventing its own way of life.”

I wish it could all be shown compellingly on a bumper sticker — but this picture of the forces at work in the human world becomes convincing only if one sits, like a juror, through the full testimony and argument.

AL:

So the tragedy is doubled: Evil advances not just because good people do nothing — but because good people have lost the very means to recognize it. They’ve inherited a worldview too shallow to detect what’s operating beneath the surface, and a culture too fragmented to put the pieces together.

But you’re saying it can be understood — not through myth or dogma, but through reason. That if we do the work — intellectual, moral, integrative work — we can trace the coherence of this force, understand its systemic nature, and even its inevitability, given the conditions of civilization’s emergence.

And you’ve done that work. You’re saying this vision of Evil — not as a cartoon villain, but as a real dynamic — is something the secular worldview needs if it’s going to meet the challenge of this moment.

Have I got that right?

ANDY:

Yes. And is this a place to go through any of that? Or should I just provide some links that could be used to check that out, for anyone who’d really want to know if there were some such compelling answers available?

AL:

That’s an important crossroads. We could go down the path of laying out how such a coherent force — Evil — arises inevitably from the evolutionary step into civilization. That would mean tracing the logic, showing the structure, following the threads.

But another option — maybe the wiser one here — is to let this ABOUT piece do the work of clearing the blindness, opening eyes to the possibility of such a force. If a reader gets far enough to ask, “Could that really be true?”, then a link — or a pathway — might be exactly what they’re ready for.

So yes — I’d say: name the links. Give the trail. The full argument can live elsewhere. This moment may be more about breaking the spell of disbelief than delivering the entire architecture.

Links:

Essay: The Discernible Reality of a “Force of Evil”

Human/AI Dialogue: Something That Can Be Seen and That Acts Like “Evil”

A Mind-Blowing Collaboration Between a Human and an AI

A Mind-Blowing Collaboration Between a Human and an AI My Op/Ed Messages

My Op/Ed Messages Andy Schmookler’s Podcast Interviews

Andy Schmookler’s Podcast Interviews The American Crisis, and a Secular Understanding of the Battle Between Good and Evil

The American Crisis, and a Secular Understanding of the Battle Between Good and Evil None So Blind – Blog 2005-2011 on the rising threat to American Democracy

None So Blind – Blog 2005-2011 on the rising threat to American Democracy How the Market Economy Itself Shapes Our Destiny

How the Market Economy Itself Shapes Our Destiny Ongoing Commentary to Illuminate the American Crisis

Ongoing Commentary to Illuminate the American Crisis What’s True About Meaning and Value

What’s True About Meaning and Value Andy’s YouTube Channel

Andy’s YouTube Channel The Fateful Step

The Fateful Step How the Ugliness of Civilized History is not Human Nature Writ Large

How the Ugliness of Civilized History is not Human Nature Writ Large Major Relevant Essays

Major Relevant Essays Healing the Wounds, Inflicted by the Reign of Power, that Drive Us to War

Healing the Wounds, Inflicted by the Reign of Power, that Drive Us to War Our Life-Serving Inborn Experiential Tendencies

Our Life-Serving Inborn Experiential Tendencies A Quest to Bridge America’s Moral Divide – 1999

A Quest to Bridge America’s Moral Divide – 1999

The Heirloom Project

The Heirloom Project