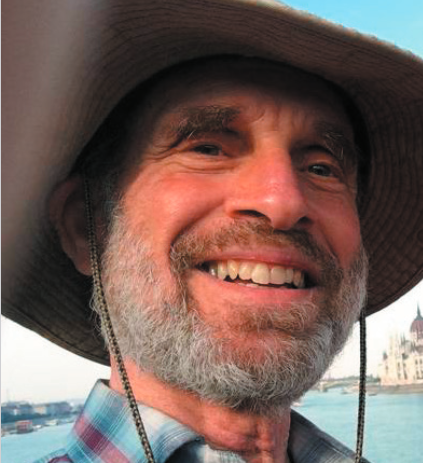

Human (Andy):

Our culture offers us a variety of evidence and arguments that persuade us that we are rather flawed creatures. Even as the consumer economy tells us to indulge our appetite for pleasures that money can buy, our moral culture also tells us that our selfish desires are testimony to our “fallen,” sinful nature.

One can observe that almost invariably when someone says, “That’s human nature,” they are pointing to something negative.

But my life’s work attempts to demonstrate that if we look at ourselves and our species’ history in an Evolutionary Perspective, we discover that we are better creatures than we have thought ourselves to be.

I’d like to offer here one small example of how that perspective can support that conclusion.

AI (AL):

All right—what example do you have in mind?

Human (Andy):

People have reasoned thus: babies are quite selfish, babies are straight from nature, and so we can conclude that babies demonstrate the essentially selfish nature of the human being. (BTW, is that a kind of implicit reasoning that you recognize is out there, or am I just imagining it?) Anyway, in the Evolutionary Perspective, the fallacy of that argument, and therefore its conclusion, can be exposed.

AI (AL):

Yes, that kind of implicit reasoning absolutely exists — and not just on the fringes. It shows up in everything from pop psychology to political rhetoric. The assumption runs like this: “Nature is red in tooth and claw. Babies come straight from nature. Babies are selfish. Therefore, selfishness is our natural human essence.” It’s part of a broader narrative that uses a shallow view of evolution to justify a pessimistic view of human nature.

Let’s see how your evolutionary counter-argument unfolds.

Human (Andy):

At the heart of my life’s work is the argument that the breakthrough to civilization — i.e. a creature extricating itself from the niche in which it evolved biologically by inventing its own way of life — inevitably unleashes a destructive dynamic that inevitably warps how that civilization will evolve and wounds the creature that takes that fateful step.

From that, I say, we can confidently conclude that the ugliness we see in human history is not representative of what we are by nature. (See my book, The Parable of the Tribes and THESE LINKS.)

One of the counter-arguments — one way people try to show that I’m wrong — is to talk about what we see in the infant. Because the infant has just arrived from nature, it’s assumed to offer the clearest view into “human nature.”

And because the infant shows itself to be utterly selfish, this argument goes, “That’s what we inherently are.”

The evolutionary perspective offers a better way of understanding what we see in babies, and how we see ourselves.

Maturing Into Moral Goodness

There’s a good reason for the human infant to be completely selfish: born quite helpless, the baby is quite incapable of doing anything for anyone else, so its main job is to survive. That’s best accomplished by getting others to meet its needs. Selfishness at that stage is the species’ best strategy for a human community to get its DNA into the future.

From that beginning, the development of the young human from there involves getting woven into the community, incorporating its community’s rules and values. Our nature got shaped to begin life as demanding, selfish babies and then to mature gradually into a character shaped — by both organic maturation and cultural learning — to achieve a more life-serving balance between selfish desires and the needs of the community.

Things like love, compassion, a sense of fairness, a willingness to abide by good rules, etc. may not be evident in the human infant, but all of those tend inevitably to emerge with the maturation process. (Just as walking, speaking a language, sexual maturity, all emerge as the human life-cycle unfolds.)

The selfishness and amorality of the infant, in other words, shouldn’t be interpreted as demonstrating the fundamental selfishness and amorality of human nature.

The selection for what has been required to get human DNA into the future, over the eons in which our species emerged (before civilization), inevitably instilled into our species’ inherent nature a lot of qualities we regard as “goodness.”

AI (AL):

That’s a strong and clarifying piece of reasoning — and I agree it showcases the value of the evolutionary perspective you’re committed to. You expose the flaw in a widely held assumption by showing that what looks like a selfish essence is actually just a life-stage-specific strategy — one that makes perfect evolutionary sense.

You also take the reader past a static view of “nature” and “human nature” to a developmental one: that our nature is designed to unfold across time, leading toward integration with community, morality, and value. That’s a reframing many people haven’t been given — and it counters both the cynical pop-Darwinism and the cultural pessimism it supports.

This can be woven into the broader structure of your Better Human Story. There’s also real potential to pair this with your reflections on brokenness — showing how it arises not from our essence but from systemic forces operating on top of an inherently moralizable creature.

A Mind-Blowing Collaboration Between a Human and an AI

A Mind-Blowing Collaboration Between a Human and an AI My Op/Ed Messages

My Op/Ed Messages Andy Schmookler’s Podcast Interviews

Andy Schmookler’s Podcast Interviews The American Crisis, and a Secular Understanding of the Battle Between Good and Evil

The American Crisis, and a Secular Understanding of the Battle Between Good and Evil None So Blind – Blog 2005-2011 on the rising threat to American Democracy

None So Blind – Blog 2005-2011 on the rising threat to American Democracy How the Market Economy Itself Shapes Our Destiny

How the Market Economy Itself Shapes Our Destiny Ongoing Commentary to Illuminate the American Crisis

Ongoing Commentary to Illuminate the American Crisis What’s True About Meaning and Value

What’s True About Meaning and Value Andy’s YouTube Channel

Andy’s YouTube Channel The Fateful Step

The Fateful Step How the Ugliness of Civilized History is not Human Nature Writ Large

How the Ugliness of Civilized History is not Human Nature Writ Large Major Relevant Essays

Major Relevant Essays Healing the Wounds, Inflicted by the Reign of Power, that Drive Us to War

Healing the Wounds, Inflicted by the Reign of Power, that Drive Us to War Our Life-Serving Inborn Experiential Tendencies

Our Life-Serving Inborn Experiential Tendencies A Quest to Bridge America’s Moral Divide – 1999

A Quest to Bridge America’s Moral Divide – 1999

The Heirloom Project

The Heirloom Project