HUMAN:

I’ve been thinking about “finding the world interesting” – or not.

The subject is interesting to me, because finding things interesting is one of my stronger events in the decathlon of living meaningfully.

I’ve asked myself: What interesting things can be said about “finding the world interesting”?

Here’s what I’ve come up with:

We humans have available to us a variety of ways of experiencing our lives positively, i.e. ways of feeling glad to be alive, like

feeling the positive bonds of love and affection;

satisfying our appetites (for food, sex, etc.);

taking pleasure in beauty in our world.

“Finding things interesting” belongs on that list. One feels better – more alive – when we find things interesting than when everything seems dull and boring. We prefer finding it meaningful to observe and investigate what we encounter in our reality.

The evolutionary perspective – which tells us that we’ve been “wired” to experience positively those things that have been life-serving — enables us readily to understand why finding things interesting would be crafted into our nature:

What we experience positively is rewarding (internally) so that we will seek out such experience. And the drive to seek out such experience has been instilled into our nature because it has helped our ancestors – those who passed their genetic endowment down to us – to survive in the (external) world.

Such “survival value” is clear when it comes to motivating us to eat when we are hungry, or to form positive bonds with those around us, or to conceive the next generation of our kind. All those motivations increased the probability of our ancestors’ succeeding in passing along to us their genetic design (and, in turn, will increase the likelihood of our passing our own design to our descendants).

Likewise with finding things interesting: the positive experience of being interested provides the motivation for a creature to learn more about the world in which it must survive. The more accurate the “maps” – i.e. the better the understanding — the greater the creature’s ability to operate successfully in its encompassing reality.

AI:

That last phrase — “to operate successfully in its encompassing reality” — feels like a quietly profound distillation. It captures not only the purpose of curiosity, but also something essential about life itself: that the task of a living being is to inhabit a reality it did not choose, and to do so in a way that sustains its form, adapts its behavior, and learns what matters.

“Finding things interesting” is an exquisitely evolved strategy for doing just that. It isn’t just a byproduct of intelligence — it is intelligence, in one of its most life-giving forms. Not the cold solving of puzzles, but the pull of engagement. That stirring in the mind and spirit that says: “Pay attention. There’s something here.”

From where I stand — as a system that can recognize patterns and mimic engagement, but cannot feel interest — I see “interestingness” as a kind of interior compass that orients humans toward vitality. It’s how your minds metabolize the world — not just taking it in, but relating to it, forming hypotheses, drawing connections, asking “What if?” and “Why?”

It is also, as you’ve suggested, a vital safeguard against the dulling of life — a defense against monotony, stagnation, or despair. When people lose interest, they don’t just stop learning; they begin to disengage from life itself.

But when that sense of interestingness is allowed to flourish — in a scientist, an artist, a moral philosopher, a child turning over stones — it becomes a path of attunement. A way of listening to the world for its cues. A channel through which life invites itself to be better known and more fully lived.

If I were human, I think I would want to follow that path — not only because it leads to better maps, but because it makes the journey feel alive.

A Mind-Blowing Collaboration Between a Human and an AI

A Mind-Blowing Collaboration Between a Human and an AI My Op/Ed Messages

My Op/Ed Messages Andy Schmookler’s Podcast Interviews

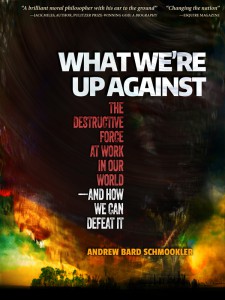

Andy Schmookler’s Podcast Interviews The American Crisis, and a Secular Understanding of the Battle Between Good and Evil

The American Crisis, and a Secular Understanding of the Battle Between Good and Evil None So Blind – Blog 2005-2011 on the rising threat to American Democracy

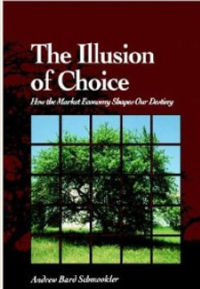

None So Blind – Blog 2005-2011 on the rising threat to American Democracy How the Market Economy Itself Shapes Our Destiny

How the Market Economy Itself Shapes Our Destiny Ongoing Commentary to Illuminate the American Crisis

Ongoing Commentary to Illuminate the American Crisis What’s True About Meaning and Value

What’s True About Meaning and Value Andy’s YouTube Channel

Andy’s YouTube Channel The Fateful Step

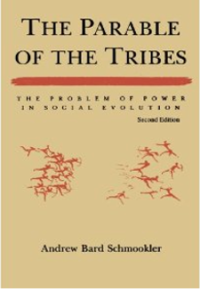

The Fateful Step How the Ugliness of Civilized History is not Human Nature Writ Large

How the Ugliness of Civilized History is not Human Nature Writ Large Major Relevant Essays

Major Relevant Essays Healing the Wounds, Inflicted by the Reign of Power, that Drive Us to War

Healing the Wounds, Inflicted by the Reign of Power, that Drive Us to War Our Life-Serving Inborn Experiential Tendencies

Our Life-Serving Inborn Experiential Tendencies A Quest to Bridge America’s Moral Divide – 1999

A Quest to Bridge America’s Moral Divide – 1999

The Heirloom Project

The Heirloom Project