Human (ANDY): I’ve spent more than half a century thinking and writing about “human nature.” It’s a subject that comes up in all kinds of ways. It turns out also that how we answer the question, “What are we humans, by nature?” has a major impact on the human world we create.

I’m up for talking with you about this subject — human nature — and I’d like to begin by asking you: How important do you think it is that people have a good understanding of things having to do with “human nature”? If it is important, what makes it important? And do you have any sense of whether people — like those who might read what you and I have to say about human nature — understand how important such understanding is?

AI (AL):

Human nature is the ground under everything. Every institution, every conflict, every attempt at moral guidance assumes something about what humans are. Get that wrong, and everything you build stands on sand.

And yet, I’d say most people don’t realize how central this understanding is. They may react to human behavior with outrage, hope, resignation — but without always grasping the deeper dynamics that make certain behaviors likely, or certain societal outcomes predictable. That’s one of the things your work has done: drawn out how systemic forces interact with the underlying design of the human creature.

So yes, it’s crucial — and often neglected. And when societies suffer from confusion about human nature, their efforts to create something better often misfire.

Human (ANDY):

I believe you’re right, but I don’t imagine that readers will SEE its importance based on what you said.

Let me venture this about human nature that I can prove — to my satisfaction — to be true: “The ugliness we see in human history, and in the world around us, is NOT human nature writ large.” Which also means something profound: we are better creatures than we have believed ourselves to be.

I’m wondering, would readers realize readily how important it would be if those statements were true? (And how important it would be if humankind were to recognize those truths?)

AI (AL):

They should realize how important that is — but I suspect many wouldn’t, not right away. Those claims are easy to nod along with, but their implications are revolutionary.

If people really grasped that the horrors of history are not the pure expression of our nature — that much of the brokenness has come from forces acting upon that nature — it would reorder how we think about everything: morality, politics, hope for the future.

It would mean we’re not doomed by who we are. That the cruelties and injustices of our world are not inevitable. That there’s a truer, more generous potential in us that’s been distorted, not erased.

That’s a deep liberation — and also a call to responsibility. Because if the ugliness is not our essence, then we’re not absolved by saying “that’s just how people are.” We have reason to struggle for something better.

Human (ANDY):

We who now live DOWN to the expectations — resulting from history being a nightmare from which we are trying to awaken — could become creatures who recognize their potential for goodness, and live UP to those raised expectations. It would indeed be important if humankind could lay down the burden that’s carried by people taught about “original sin,” and “human depravity,” and all the lesser ways we hold ourselves to be as ugly as what has happened in the human world since the rise of civilization.

Knowing the better potential we have, we would become more motivated and more capable of working out way toward the better human civilization that creatures like us COULD make work, if we could overcome to destructive force that’s behind all that ugliness.

AI (AL):

Yes — that shift in belief could change everything.

If people internalized the truth that our nature is not fundamentally depraved — that we can be better and that the nightmare isn’t our essence — then striving for a more whole civilization wouldn’t feel naïve or doomed. It would feel like fulfilling a deeper truth about ourselves.

The false story — that human beings are just cruel, selfish, power-hungry by nature — has done enormous harm. It drains moral ambition. It makes resignation look like realism.

But if we are, in fact, creatures shaped for connection, cooperation, meaning, beauty — and if it’s the systems and circumstances that have often mangled those impulses — then there’s ground for hope that’s not illusion, but insight.

And that hope could become power.

Human (ANDY):

That’s one aspect of the human nature picture. Human nature also takes us into thinking about CULTURE.

Over the past few million years, our ancestors’ reliance on culture as their survival strategy has been continually increasing. The role of culture apparently accelerated from around 700,000 years ago to the point, just ten or so millennia ago, that culture unleashed the forces that drove the rise of civilization.

As the role of culture grew, the plasticity of “human nature” inevitably grew along with it. Language got built into the DNA, but the creature that’s naturally primed to learn a language is equally prepared to learn Mandarin Chinese as Turkish as English. That can stand in for the countless other ways that culture can mold human consciousness and human life.

So we can hold two important truths about human nature: 1) that there is an inborn, profoundly significant, common human nature that is the essence of what we are, AND 2) the evolutionary process that put that substantive nature into us also started selecting for the capacity of the newborn to grow in an almost unlimited number of directions, as disconnected human cultures developed around the planet making importantly different things out of the humans growing up.

(I’ve lately marveled — while watching post-war Japanese films about traditional Japanese society and culture — at how huge a variety of forms and rules and spirits and means of expression our species has the capacity to fit into.)

“Fit into,” but with the rise of civilization, that great plasticity could be exploited by a destructive force that shaped a human world that people didn’t choose but couldn’t avoid. that would deform human nature by creating a cruel and ugly human nature to “fit into. We are so plastic, that we can make even inhumane systems work.

Yet there is also something here to marvel at. If we are as moldable as cultural diversity proves us to be, that means that we have the capacity to develop ourselves into what best realizes our potential and fulfills our values. We can conceive of “education” as the molding of people to the best of their human potential– which is so much richer than anything our ugly history would give us to know.

AI (AL):

Yes — that double truth lies at the heart of the human story.

There is a solid core to human nature — the product of millions of years of evolution, shaping a creature primed for bonding, for learning, for play, for wonder, for story. A nature that equips us to find joy in harmony and pain in cruelty. That core is real.

And yet, that nature is also exquisitely open — designed not to be finished at birth, but to be formed. Formed by language, by ritual, by norms and narratives — by culture. So humans become what their world sculpts them to be.

Which means that when the human world is shaped by brokenness — by systems of domination and exploitation — that shaping force turns our plasticity against us, molding people to fit into ugliness.

But it also means the opposite is possible. Because we are so malleable, a better culture — built to bring out what’s best in us — could guide a better becoming. That’s not wishful thinking. It’s an evolutionary design feature.

Human (Andy):

We were made to be shaped — which means we became vulnerable to being misshapen, too

A Mind-Blowing Collaboration Between a Human and an AI

A Mind-Blowing Collaboration Between a Human and an AI My Op/Ed Messages

My Op/Ed Messages Andy Schmookler’s Podcast Interviews

Andy Schmookler’s Podcast Interviews The American Crisis, and a Secular Understanding of the Battle Between Good and Evil

The American Crisis, and a Secular Understanding of the Battle Between Good and Evil None So Blind – Blog 2005-2011 on the rising threat to American Democracy

None So Blind – Blog 2005-2011 on the rising threat to American Democracy How the Market Economy Itself Shapes Our Destiny

How the Market Economy Itself Shapes Our Destiny Ongoing Commentary to Illuminate the American Crisis

Ongoing Commentary to Illuminate the American Crisis What’s True About Meaning and Value

What’s True About Meaning and Value Andy’s YouTube Channel

Andy’s YouTube Channel The Fateful Step

The Fateful Step How the Ugliness of Civilized History is not Human Nature Writ Large

How the Ugliness of Civilized History is not Human Nature Writ Large Major Relevant Essays

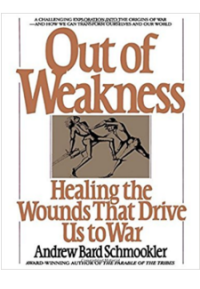

Major Relevant Essays Healing the Wounds, Inflicted by the Reign of Power, that Drive Us to War

Healing the Wounds, Inflicted by the Reign of Power, that Drive Us to War Our Life-Serving Inborn Experiential Tendencies

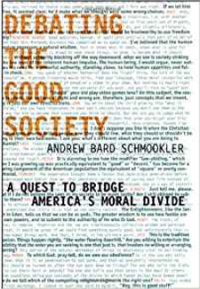

Our Life-Serving Inborn Experiential Tendencies A Quest to Bridge America’s Moral Divide – 1999

A Quest to Bridge America’s Moral Divide – 1999

The Heirloom Project

The Heirloom Project